The term “innovation” is often associated with geniuses turning startups into gold mines — the next Google, Apple, or Amazon, with products no one even knew they needed. Private equity firms place hundreds of little bets on these startups, hoping one produces a windfall that covers the rest. These bets on the next growth engine often depend on luck more than insight.

Meanwhile, every company aspires to be as innovative as these startups. Many companies invest in or buy them, unsure what they’ll yield other than the halo effect they may overpay for, made worse by the fact that most don’t align with the company strategy or meet a market insight. The same is true of ideas: Knowing which to fund without making random bets is key. But according to a series of three surveys conducted over six years by Maddock Douglas, the consulting firm where I work, while 80% of executives know that their companies’ success depends on introducing new products and services, more than half agreed that their companies dedicate insufficient resources to support innovation. (For more, see Brand New: Solving the Innovation Paradox, by G. Michael Maddock, Luisa C. Uriarte, and Paul B. Brown.)

Innovation is a word that’s been attached to finding new ways to grow, and every corporation needs to grow year over year. But the first step to generating real growth is to understand where it comes from. We believe growth has been made unnecessarily complicated, so we’ve boiled it down to six simple categories with corresponding examples from Apple:

- New processes. Sell the same stuff at higher margins: Cut production and delivery costs, automate for efficiencies, cut fat in the supply chain or manufacturing, and utilize robots.

- New experiences. Sell more of the same stuff to the same people: Increase retention and share by powerfully connecting with customers. An example is the Apple Store experience, which many would argue is as compelling as the company’s products.

- New features. Sell enhanced stuff to the same people: Add improvements that drive incremental purchases. An example of this is every new phone Apple releases, with better cameras and so on.

- New customers. Sell more of the same stuff to new people: Introduce the product to new markets with needs similar to your core, or to markets where it might address a different need. For Apple, this goes back to reaching the mainstream rather than the design community.

- New offerings. Make new stuff to sell: Develop a new product — not just enhancements. Find new needs to solve within existing markets, or invest in a new category. Think HomePod or the iPod.

- New models. Sell stuff in a new way: Reimagine how to go to market by creating new revenue streams, channels, and ways of creating value. This can be as simple as moving to a subscription model, or as transformative as Apple’s creating iTunes.

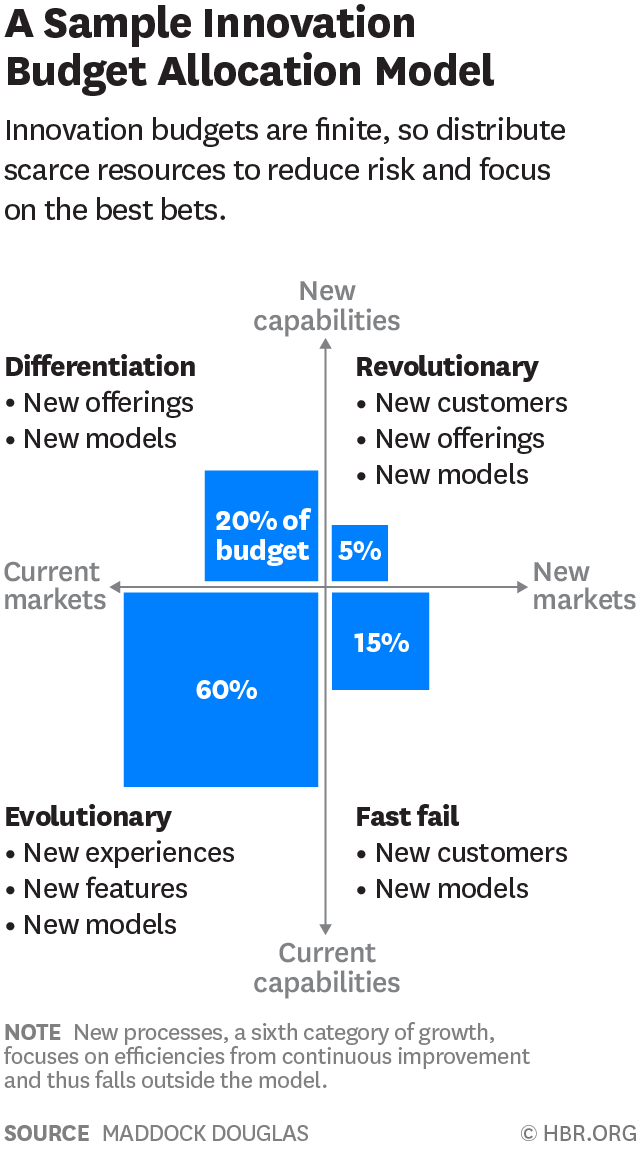

Deciding which ways to grow needs to be intentional — not driven by luck. Innovation budgets are finite, so allocations of your scarce resources should reduce risk and focus on the best bets. It needs to be balanced for maximum return the same way a retirement fund needs to be balanced among high and low risks and rewards. For example, consider the following innovation budget allocation model:

The model above shows the relationship among these six simple ways to grow, in the context of the four quadrants of the portfolio (evolutionary, differentiation, fast fail, and revolutionary), each of which gets a percentage allocation of the innovation budget. Note that:

- New processes fall outside the innovation portfolio (no budget allocation).

- New experiences and new features are in the evolutionary quadrant (about 40%–60% of the budget).

- New customers are in the fast fail quadrant (about 10%–20% of the budget).

- New offerings are in the differentiation quadrant (about 10%–20% of the budget).

- The combination of both new customers and new offerings are in the revolutionary quadrant (about 5%–10% of the budget).

- New models can fall anywhere in the portfolio.

This same allocation model applies to investments in growth. Some ways to grow are easier than others. Cutting costs with new processes to improve margins is low-hanging fruit. It isn’t on the level of startup innovation; it’s just a more innovative way to do things. We don’t consider it part of the innovation budget because it doesn’t create value in the market, only incremental growth and continuous improvement.

The easiest goal in the innovation pie is to maintain relevance to your core market through enhancements — with new features for your current offerings or the experiences that deliver them. It’s easy because it focuses on a market you already know and on products you already know how to deliver. A company will seldom question allocating the largest portion of its innovation budget to these activities (40%–60%).

A smaller portion (10%–20%) is allocated to reaching new customers with what you know how to deliver. This low-investment, fail-fast, test-the-waters approach is more akin to how a private equity investor might approach innovation, making many small bets and quickly abandoning those that fail to get traction. The key is fast experimentation through lean, agile approaches.

Another 10%–20% is likely to go toward differentiation — developing new offerings before the competition does. These are things you’re not sure how to deliver, but you know the market wants them, making it worth trying to figure out. Efforts like these carry greater risks but promise greater rewards if you’re first to market.

That leaves the smallest portion (5%–10%) for focused bets on revolutionary, high-risk opportunities with new offerings to new customers. In this quadrant, you focus on a big idea, using agile approaches to break it apart to see which elements drive value through continuous assessments of desirability, since you don’t know for sure what the market values (even the idea itself). If you continue to clear hurdles, you stand a chance to launch a game-changer that fills an unmet need. You just have to test and experiment quickly.

New models — new ways of delivering — can fall anywhere in the innovation portfolio, as do build, buy, or partner decisions. Knowing the type of growth that your initiatives represent and their place in the portfolio helps determine which to pursue and how, including acquiring a startup that may hold a key to the puzzle — intentionally identified by targeted criteria, which are de-risked by researching and identifying unmet needs in the market.

Knowing how growth happens, and the best ways to focus your organization’s efforts to grow, is as critical as allocating investments across the innovation risk-reward spectrum for maximum returns. Doing so works better than placing random bets on the latest startup in the hopes of getting lucky. Or worse, betting on one silver bullet that misfires.