It’s a well-known paradox. Most executives are committed to the idea of maximizing long-term shareholder value, but when they want to track and improve performance, they focus on a dizzying variety of short-term measures (and acronyms). ROA. ROC. TSR. EBIT. EBITDA. CAR. EPS. We could go on.

Why this focus on short-term measures? In large part, because they’re easy to obtain, easy to use, and have been widely used in the past. The problem, as studies have long made clear, is that optimizing short-term accounting measures and ratios often doesn’t maximize long-term value. To think clearly and effectively about long-term value, companies need a better measure — and, as we write in a recently published article in the Strategic Management Journal, we’ve devised one that we call LIVA, short for Long-term Investor Value Appropriation.

The idea behind LIVA is simple: Add up the net present value of all the investments a firm has engaged in over a long period of time. The key insight from our analysis is that this can be done by using publicly available stock-market data. LIVA uses historical share-price data to calculate the value a company has either created or destroyed for its entire investor base over a long time period.

To see what LIVA can do, consider the case of Apple. Imagine you were fortunate enough to have bought 100 shares of the company’s stock in 1999. If you had reinvested any dividends and sold your shares 20 years later, you would have made an annualized return of 27%, well above the market average of 6%. That’s a healthy return, but hardly spectacular. In terms of total shareholder returns (TSR), it ranks 3,175th among companies worldwide over this time period — a ranking that would seem to suggest that Apple’s success hasn’t been very exceptional. One might derive the same conclusion from the most recent “Value Creators Rankings,” published annually by the Boston Consulting Group, which is based on five-year TSR and ranks Apple #34.

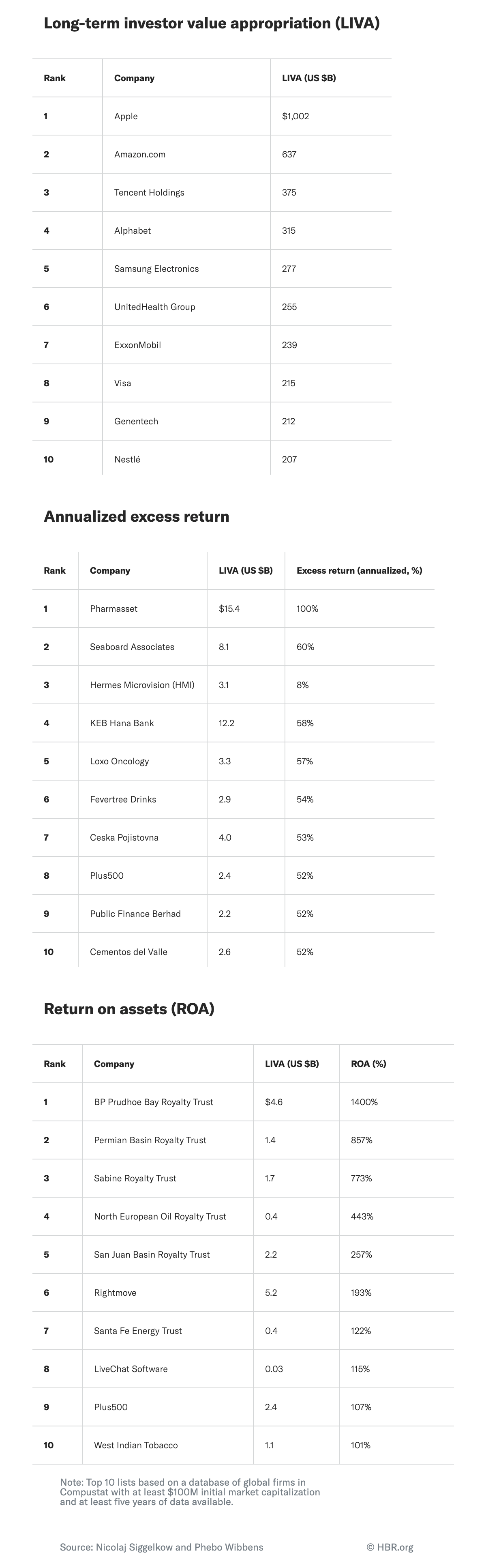

The problem is that TSR doesn’t actually measure long-term value creation for the entire shareholder base over a particular time period, but only the returns for those who held (a certain number of) shares over the entire period. LIVA, however, takes into account that the capital base of a company can change over time. In doing so, it provides a very different sense of the value Apple has created. If in 1999 you had bought the entire company at its then-market price, accounted for any cash received through dividends or share buybacks, and gone on to sell it 20 years later at its much-improved market price, you would have been more than a trillion dollars richer than if you had invested the same amount of money in an index fund. Apple’s LIVA over this period, in other words, was more than $1 trillion. That’s truly dominant performance that makes Apple the world’s number-one company in our ranking, with a LIVA 57% higher than that of Amazon, our number-two company.

Those rankings come from a global LIVA database we’ve created to help managers and researchers identify the best- and worst-performing companies by country, region, and industry. The database tracks the performance during the past 20 years of more than 45,000 companies that had at least $100 million of initial market capitalization and for which data was available for at least five years. It allows analysis of value creation at the level of individual companies, industries, and countries.

A comparison with traditional performance measures shows how much more revealing LIVA is, as becomes clear when you look at the top and bottom 10 performers as determined by each method.

Value Creators: The Global Top 10

The top five companies on our LIVA list are tech companies that together have created more than $2.6 trillion in shareholder value in the past 20 years. If you look at the top companies on the excess-return list, you’ll see that although successful, they haven’t generated anything like that kind of value. They were able to achieve very high returns, in fact, only because they started out small, with an initial average market capitalization of $332M. For example, the market capitalization of the number-one company on the list, Pharmasset, was $187M in 2007 and shot up to $11.2B in 2011, when it was acquired by Gilead. (We’ve excluded companies with less than $100M in market capitalization; their inclusion would certainly lead to even higher potential figures of excess returns.)

The top performers on the ROA list are also relatively small companies. That’s because an extremely high ROA often does not reflect very high profits but rather very low balance-sheet assets. The top performer on the ROA list is BP Prudhoe Bay Royalty Trust, a company that distributes profits from oil- and gas-royalty rights, which have not been capitalized on the balance sheet to their economic value. The company’s apparently high performance is thus as much a reflection of accounting conventions as of good underlying economic performance.

These examples show some of the potential advantages of using LIVA when assessing long-term firm performance. Unlike measures based on ratios such as ROA, LIVA determines the absolute size of economic performance without favoring initially small companies. Unlike accounting-based return measures, it values both profits and growth. And it never hinges on accounting definitions.

If you were to look at just the 10 best LIVA performers, you might conclude that tech is the place to create value. But one of the great advantages of LIVA is that it provides revealing information not only at the top but also at the bottom.

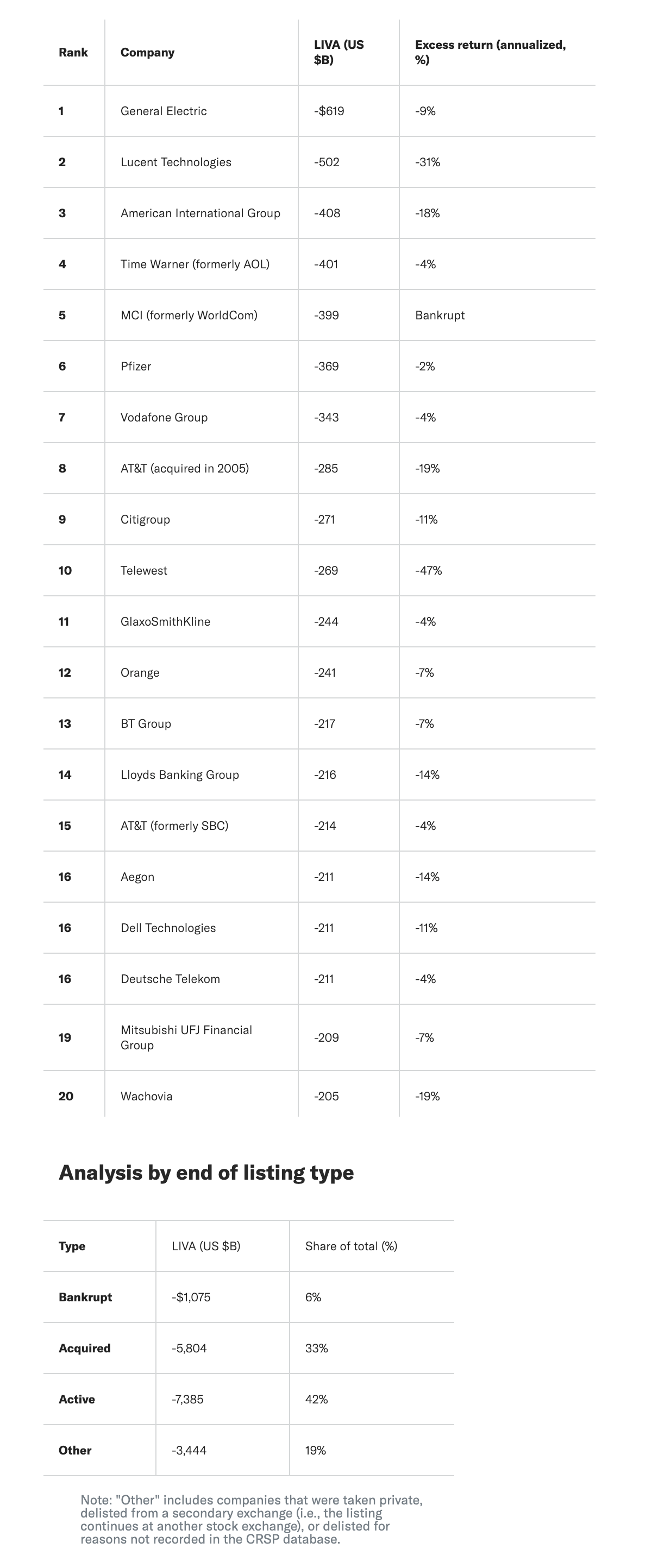

Worst Performers: The Global Top 20

If you look at the worst performers on our list, you’ll notice several tech companies: Lucent, MCI/WorldCom, and AOL/Time Warner. These companies have destroyed a remarkable amount of value in the past 20 years. In fact, in the aggregate the companies in the category Technology Hardware & Equipment in our database had a LIVA of negative $2.2 trillion. The only category that has destroyed more value is Telecommunication Services. Other measures don’t reveal the extreme distribution of long-term performance in the tech industry that our LIVA measure reveals — nor, by extension, do they prompt questioning about why that distribution exists in the form it does. A LIVA analysis reveals that a majority of companies in the tech industry actually destroy value. Only those companies that dominate their respective sectors are able to create enormous shareholder value — a consequence of network effects.

LIVA also provides a more meaningful way to think about bankruptcy than total shareholder return and excess return do. In bankruptcy, after all, unless there is residual value to claim for shareholders, those measures are always the same: −100%.

LIVA details the magnitude of the value destroyed in each case and therefore can serve as a meaningful measure with which to analyze corporate decline. In this context, a striking fact emerges when one uses LIVA to study the companies in our database: Only one of our top 20 value destroyers actually went bankrupt. It turns out that 42% of the value destroyed from 1999 to 2018 was destroyed by companies that were still active in 2018, and another 33% was destroyed by companies that were acquired. Companies that were once successful often have a much longer time to destroy value than firms that go bankrupt. If value destruction is a form of “failure,” then most of the failure is happening at firms that still exist. This suggests that LIVA might be a valuable addition to the bankruptcy and dissolution measures used regularly in industry-life-cycle and population-ecology studies.

To create long-term value in the future, managers need to understand what strategies have been successful in the past. LIVA provides a robust tool for knowing which companies in various countries and industries have been able to create the most value and which have destroyed it. With internal financial data, managers can use LIVA to identify the strategies in their own companies that have paid off the most — an indispensable lesson that can help them lead their companies and hopefully join the ranks of the global top LIVA creators themselves.

Editor’s note: Every ranking or index is just one way to analyze and compare companies or places, based on a specific methodology and data set. At HBR, we believe that a well-designed index can provide useful insights, even though by definition it is a snapshot of a bigger picture. We always urge you to read the methodology carefully.